The Gang of Five

Gentle Readers,

Your indulgences. This is a long entry, and as such probably breaks all the rules of blogdom. Are there rules?

My young friend, Juhi, asked me to recommend a few books to her. I went off the deep-end and produced the following:

November 30 – December 12, 2005

Hyderabad, India

Dear Juhi,

Thanks for asking me to recommend a few books to you. What sounded like a very simple request became more and more complicated as I thought about it, and I’m afraid I’m going to stick you with a hybrid of book list and memoir that goes on much longer than I thought it would.

More than any other activity, reading has been a constant in my life. Some time before I began pre-school, and I have no idea why I had the urge, I begged my parents to teach me to read. Thinking they were doing the right thing by not wanting me to get ahead of my peers, they told me that as soon as I started school I’d be able to read. I awaited the day. According to family legend I returned home after my first day of school, picked up a book, and sat myself down – ready for the great adventure to begin. Within minutes I was desolate, and in tears. The marks on the page were as incomprehensible as ever – I had been betrayed. A day of school had gone by, and still I could not read. Of course, I recovered, and family legend continues that I actually learned to read on road trips by puzzling out the advertising on bill-boards along the roadside. I certainly remember the peculiar American advertisements for “Burma Shave,” a nationally known shaving cream. They were sets of six small red signs with white print, posted about 100 feet apart on rural highways, and you had to be fairly quick to spot and read them. The slogans were corny, but fun: “Doesn’t kiss you…Like she useter?...Perhaps she’s seen…A different rooster…Burma Shave!” The whole family would watch out for them, but I got to shout the slogans out.

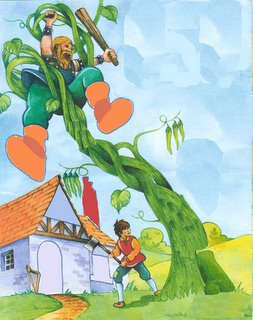

I remember only one book from my early childhood, an illustrated collection of fairy tales, and the story that stood out was that of Jack and the Beanstalk. As I recall, Jack traded the family cow for magic seeds that grew into a great beanstalk that Jack climbed to a Giant’s lair. He came across a bag of gold and thought he’d steal it to make reparation for the poorly bartered cow. Although he used all his guile, when he got close to the Giant, and the gold, he was, literally “sniffed out,” and the Giant announced his discovery with, “Fee, Fie, Fo, Fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman!” Jack eventually got the gold, and fled down the vine. The Giant gave chase, but Jack was able to take an axe to the beanstalk, and sever it, and the Giant fell to his death. The moral is a puzzle: Barter well, but if you don’t its ok to steal from a Giant – and kill him while making your get-away.

The first “young reader’s” book I read cover to cover, and I stayed up well past bed time to do it, was, “The Guadalcanal Diary,” by Richard Tregaski – a soldier’s account of a particularly awful series of battles in the South Pacific during World War II.

The first book I ever purchased was, “Al Capone,” a biography of the American gangster – one of the first of the Mafiosi. What a cast of characters, and what names: Dion O’Banion, Big Jim Collosimo, Frank Nitty, and Big Al himself. Really bad guys, and I’m still fascinated by the history of organized crime.

As a “good, Catholic,” boy I also read voraciously in Butler’s “Lives of the Saints.” These were supposed to be moral tales describing the trials and victories of leading a Christian life, but for me, they were an enthralling, almost pornographic compendium of torture. Many of the stories had to do with the fate of virgins who protected their chastity at all costs, and “soldiers of Christ” who refused to renounce the faith. So many saints dismembered, decapitated, eye-gouged, boiled in oil, stretched on the rack, riddled with arrows, and stoned; an endless, mind-boggling, and particularly juicy list to an over-imaginative youth.

I don’t recommend any of the above, except, perhaps, (and slightly facetiously,) the “Lives of the Saints,” for a look into how weird religious teaching can be.

Fairy tales, war, gangsters, and mutilated saints – what a foundation for a life of reading. And it has been a life of reading in which I’m sure I’ve read at least a book a month (more, really,) since the primer of, “See Jack run…” And what an adventure it’s been. I’ve witnessed the creation of matter; have had a look at the farthest reaches of the universe, and through all the permutations of human behavior committed to print!

All of which leads me to a total lack of confidence in recommending a course of reading, or even a simple suggestion of, “You ought to read…” Yes, of course, there are individual books that have moved and shaped me, but they were particular for a time and a need, and it would be presumptuous of me to determine your time or need, or to waste your time with even the first fifty pages of something you might find totally irrelevant.

Instead, I’d like to tell you about the authors who have captured me for a lifetime, mention the work that led me deeper – even if it may not be the best of their oeuvre, and let you take it from there.

But first, what is it about authors, and was I attracted to the literature because of the author, or to the author through the literature? It turns out a combination of both, but, oh, how I loved those authors.

Why?

I wrote above that I was a, “good Catholic boy,” and that’s true enough, but without enough truth.

I was baptized, and raised a Catholic, went to church, received the sacraments, but from the age of seven to fourteen it was all a painful charade. The difficulty came because I was a six-year-old Casanova, and spent a lot of time with the neighborhood girls, “playing doctor,” as it was then called. The play was really about discovering, and enjoying our forbidden bodies – our forbidden sexuality. No religion is comfortable with pleasure, especially physical pleasure, Catholicism is no different, and we knew our play was out-of bounds. We certainly knew enough to keep it hidden in the secret corners of the neighborhood.

Matters were made worse for this “good Catholic boy,” because at age six I was being formally prepared to enter the, “age of reason,” the magic age when we were told we would understand the difference between good and evil, and be expected to live our lives accordingly. This passing from innocence to experience is a Catholic’s first conscious rite of passage, and is part of the genius of the religion.

The preparation for this step into reason was a detailed study of Christianity’s moral code – the Ten Commandments, and indoctrination into an exercise called the “examination of conscience,” in which we reflected on how we may have transgressed. Practical application came by way of a confession of sins, followed by our “First Holy Communion,” at which time we imbibed the mystical body and blood of the Lord, Jesus Christ. The ritualized cannibalism was the easy part. The hard part was the confession of sins during which we met, individually, with a priest, and on our knees detailed our wrong doings, and begged forgiveness; but forgiveness was not assured, and was contingent on honesty in the telling, and sincerity in the repentance. And, there was a fail-safe of sorts to keep us honest: an incomplete or insincere confession was classified as a “mortal sin.” “Mortal,” as in “fatal.” Not physically fatal, but fatal to our souls. If I were to die with a mortal sin staining my soul, my spirit would be cast into hell, there to suffer for eternity. Hell was presented as a real place, and our teachers even claimed the existence of maps – influenced, no doubt, by hell’s great cartographer, Dante.

Embarrassment and fear kept me from telling the priest about my sexual adventures.

I then compounded the matter by taking Communion, thus committing another mortal sin, and repeated the cycle every Confession Friday and Communion Sunday for the next seven years.

I was no longer in a, “state of grace.”

I was doomed.

Redemption has been an obsession ever since. Redemption marks the return to grace. The authors I’m going to mention have all dealt with the urge toward redemption; and I dare say great art is motivated by our need for redemption, be it from “original sin-“ the legacy of the original Fall - sins of the flesh, or sins of the spirit.

At age fourteen Catholics undergo another rite, in which your faith is confirmed, and it’s known, aptly enough, as “Confirmation.” Again, intense study – in fact, the entire seven years between rites were spent in various degrees of preparation – followed by a confession of sins to enter the state of grace necessary to receive the sacrament, and culminating in a public ceremony in which you were questioned as to the tenets of the faith, anointed with oil by your Bishop, lightly slapped to signify the suffering you should be prepared to experience in keeping the faith, (back to the “Lives of the Saints,”) took a new name to mark your identity as an adult Christian, and sent into the world as a “soldier of Christ.”

I was intent on coming clean before I was confirmed. I was intent even as I approached the priest. I was intent as I knelt…and I was devastated as I walked away having failed to summon the courage to rescue my soul. Then, as if in a dream, I went through the ritual motions of confirming a faith that God and I knew I was not strong enough to embrace.

Life pretty much went to hell from there.

I was an adopted child (a whole other story,) and always felt as though I were an outcast. I had failed my religion, and compounded mortal sin upon mortal sin – I was sure that I was excommunicated from the Church, even if ex officio – outcast again – outcast and doomed. Later that year my step-father died, and I was again abandoned.

Abandoned, outcast, and doomed.

The stories I’ve told thus far would probably lead you to believe I was an abnormal child. I don’t think that’s so. I was well loved, my family was well off, and I was engaged in most of the same activities any 7 to 14 year old boy would enjoy. But, I don’t think there’s any accounting for the secret life of childhood and adolescence, and my secret life was fraught with moral and existential dilemmas of an adult level.

I found what I thought were an equally doomed group of friends, and our escape hatches were between book covers, and under bottle caps.

Abandoned, outcast, doomed, and drunk; I found Eugene O’Neil.

Geoff Peterson introduced O’Neil into my life. Geoff was one of my best friends, and we were both interested in the theater. He had hooked up with the local college drama department, and I followed him through the doors.

Geoff was playing the role of the young Eugene O’Neil in, “Ah! Wilderness,” O’Neil’s only comedy, and probably the only O’Neil that the town or college was equipped to handle. O’Neil’s work marks the beginning of serious American drama, and the best of it had to do with his miserable Irish family, or the outcasts and misfits of his equally miserable life. The New York Times described his work as, “…deep, dark, solid, uncompromising and grim.”

I loved everything about Eugene O’Neil. I loved that he was born in a hotel, and was an alcoholic from a family of alcoholics. I loved that his mother was addicted to morphine; that his father was a hack actor; and his brother a Broadway ne’er-do-well. I loved that he had shipped out with the Merchant Marine. And I loved that he suffered for his art. The name I took at my Confirmation, “Eugene,” was secretly for Eugene O’Neil. I got away with it because I had told everyone it was for the current Pope, Pius XII, whose given name was “Eugenio.”

O’Neil died in 1953, and even by then the majority of his work was dated, but the late 1950’s, early ‘60’s saw a revival of his best work. Jason Robards was the actor that embraced O’Neil in those revival years, and his status probably sold as many tickets as the plays. The roles he played were Shakespearian in proportion. There are at least three O’Neil masterpieces I’ve seen performed: “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” “The Iceman Cometh,” and, “A Moon for the Misbegotten,” and they’re beautiful and heart-breaking.

One drunken night at Jim Gallagher’s house, Geoff launched into a monologue culled from, “A Moon for the Misbegotten.” It was a bravura performance, spellbinding, and shattering. At the time we didn’t know that what he was saying was from a play – the s.o.b.

Here are the last few paragraphs:

I had to bring her body East to be buried beside the Old Man. I took a drawing room and hid in it with a case of booze. She was in her coffin in the baggage car. No matter how drunk I got, I couldn't forget that for a minute. I found I couldn't stay alone in the drawing room. It became haunted. I was going crazy. I had to go out and wander up and down the train looking for company. I made such a public nuisance of myself that the conductor threatened if I didn't quit, he'd keep me locked in the drawing room. But I'd spotted one passenger who was used to drunks and could pretend to like them, if there was enough dough in it. She had parlor house written all over her--a blonde pig who looked more like a whore than twenty-five whores, with a face like an overgrown doll's and a come-on smile as cold as a polar bear's feet. I bribed the porter to take a message to her and that night she sneaked into my drawing room. She was bound for New York, too. So every night--for fifty bucks a night--

--How could I? I don't know. But I did. I suppose I had some mad idea she could make me forget--what was in the baggage car ahead.

No, it couldn't have been that. Because I didn't seem to want to forget. It was like some plot I had to carry out. The blonde--she didn't matter. She was only something that belonged in the plot. It was as if I wanted revenge--because I'd been left alone--because I knew I was lost, without any hope left--that all I could do would be drink myself to death, because no one was left who could help me. No, I didn't forget even in that pig's arms! I remembered the last two lines of a lousy tear-jerker song I'd heard when I was a kid kept singing over and over in my brain.

"And baby's cries can’t waken her, in the baggage car ahead. And baby’s cries can’t waken her, in the baggage car ahead. And baby’s cries can’t waken her in the baggage car ahead.”

Jim and I left the room with Geoff huddled on the bed. He’d certainly managed to put a damper on the evening… When I finally found the reference, on the same record album from which Geoff had stolen it, I let it go. It was too much to bring up.

The Gallagher family was a piece of work in itself, and I spent a great deal of my senior year in high-school hanging out at their house – mostly in Jim’s bedroom. Jim’s father, Arthur, was a chronically unemployed alcoholic who spent his time lazing on the couch listening to French language radio, (though he spoke not a word of French,) and reading Spinoza. He was also our beer connection, and would charge us a six-pack for every case he picked up for us. Of course, we paid up. Jim’s elder sister was a wild-child in her own right, and Mrs. Gallagher was a hard worker who kept food on the table, and a roof over their heads, but had no control over her husband or brood. Jim was one of the doomed; a high-school neo-Nazi with a penchant toward marching songs and Gilbert and Sullivan. Once, Jim locked me in his bedroom until I could prove I’d memorized an entire Gilbert and Sullivan song from, “The Sorcerer.” The title was, “John Wellington Wells,” and Jim thought it appropriate to my name. I occasionally recite it as a party piece, to the astonishment of my friends.

Geoff and I fancied ourselves miniature Eugene O’Neil’s, but Geoff had a leg up. Not only had he acted in an O’Neil play, but he was “black Irish,” as was O’Neil, and actually wrote a couple one-act plays. I just drank, smoked, read the collected works and the definitive 800 page biography, and pretended I was as talented and rakish as the great man.

(For more on O’Neil: www.eoneill.com)

Henry Miller was an author (and watercolorist) who may not be so widely read these days. Henry was American born, of Manhattan, in 1891, and knocked around the city until 1930 when he moved to Paris to begin what were his great years of self-discovery. Miller was a Catholic who eschewed all religion and leaned toward an all-encompassing pantheism. Like all the gang Miller was the primary figure in his own works, and his works were wild, though probably wilder than the life that fueled them.

Miller wrote copiously of his sexual escapades, and came perilously close to becoming known as a writer of “dirty books,” and a parody of the dirty old man. “Tropic of Cancer,” published in France in 1934, didn’t make it to the US until 1961, and it immediately became embroiled in a series of obscenity trials finally decided by the US Supreme Court on the same day it was presented.

Miller’s trilogy, “Sexus,” “Plexus,” and “Nexus,” were, according to him, an outpouring of the vilest and most depraved imaginings his psyche could produce. I’ve not read them, but wonder in 2005 how vile they could really be.

He returned to the US in 1940, and eventually settled in Big Sur, California.

I read about “Tropic of Cancer,” well before it was released, and came across it in its original Grove Press Edition in a bookstore in New York City in 1961. I can still see the display of that shiny, red paperback, with its black title in a white circle. I didn’t purchase it because I was with my folks, and was a little afraid that showing interest would tip them off to what their kid was really thinking about, but I was thrilled to see it.

(Grove Press was one of the most courageous publishing houses in America, and enjoyed quite a bit of notoriety and profit from the American publication of, “Lady Chatterley’s Lover;” as well as most of Samuel Beckett, Jean Genet, Federico Garcia Lorca, and a host of other influential, avant-garde, and sometimes scatological authors. Most of the Grove catalogue is still in print. Grove also published, “The Evergreen Review,” arguably America’s most influential literary journal from 1957 – 1968. Grove’s publisher, Barney Rosset, on free speech: “…I feel that personally there hasn’t been a word written or uttered that shouldn’t be published.”)

I was a bit older when I finally got around to “Tropic of Cancer,” and remember “meditating” on the “good bits,” and falling in love with the grit and grime of Miller’s milieu. Here was a guy who was tromping through the muck, and having a glorious time of it.

As much as I liked, “Tropic of Cancer,” and its follow-up, “Tropic of Capricorn,” I loved Henry Miller’s essays. Miller came across as smart, comic, impassioned, and immensely likable. He seemed to like what I liked, and hate what I hated, but with so much more panache than I could ever summon.

“The Air Conditioned Nightmare,” “Stand Still Like the Hummingbird,” “Wisdom of the Heart,” are all wonderful collections, but I’ve read so much Miller, and like him so much I’d recommend just about any of his essay collections except, “The Time of the Assassins,” which is a literary study of Rimbaud, and nowhere near as compelling as his other works.

Here’s what George Orwell wrote of Henry Miller:

"Here in my opinion is the only imaginative prose-writer of the slightest value who has appeared among the English-speaking races for some years past. Even if that is objected to as an overstatement, it will probably be admitted that Miller is a writer out of the ordinary, worth more than a single glance; and after all, he is a completely negative, unconstructive, amoral writer, a mere Jonah, a passive acceptor of evil, a sort of Whitman among the corpses."

And what Henry wrote about art:

"We’re creators by permission, by grace as it were. No one creates alone, of and by himself. An artist is an instrument that registers something already existent, something which belongs to the whole world, and which, if he is an artist, he is compelled to give back to the world."

(Henry here: www.henrymiller.org)

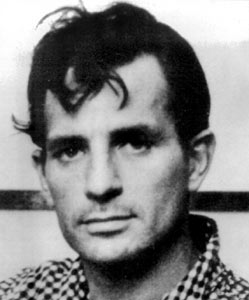

I don’t remember how I came to the beatniks, but they were the enfants terrible of American letters, and enjoyed great notoriety for their work, and their life-styles. I have to speak the names Kerouac, and Ginsberg in the same breath, though they were hugely different people, and writers. Ginsberg gives credit for the beat generation and its revolution of prosody to Kerouac. I don’t think Kerouac gives it to anyone but Dostoevsky, and God. Kerouac and Ginsberg were both, “rake and ramblin’ boys,” and I loved their bad-boy-ness as much as I admired their writing.

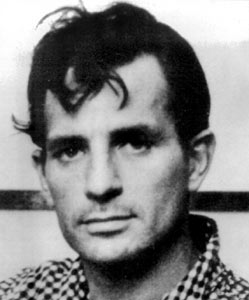

Jack Kerouac was from a French-Canadian family of Lowell, Massachusetts, and he called his work as a whole, “The Legend of Duluoz.” “Duluoz,” was not only the name he gave himself in a number of books, but also a pun for “louse,” both a bloodsucking insect, and a contemptible person. Raging alcoholic that he was, Jack had a bit of a self-esteem problem. As of 2001, 27 books comprised the legend, but new volumes tend to pop up as they’re released by his estate. About 20 years ago I took a summer to read most of his work, some of it for the second or third time, and was as enchanted as on first reading, albeit with a lot more understanding of Kerouac’s pain.

Jack worked any number of jobs to support his writing habit. I was impressed that he had been a brakeman for the Union Pacific Railroad, and had shipped out as a Merchant Marine. O’Neil and Kerouac had both shipped out – eventually I was to do the same.

Kerouac’s breakthrough, and still most widely read book was, “On the Road.” These are the adventures of Sal Paradise (Kerouac,) and Dean Moriarity (Neal Cassidy, who played an important role throughout the Legend, and the history of the beat generation.) “On the Road,” ignited Kerouac’s career, and the literary/lifestyle movement of his generation. Here’s a popular quotation:

“The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn, like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars..."

Jack wrote, “On the Road,” in a marathon session, typed on a 120 foot long paper scroll. The scroll was purchased in 2001 for 2 ½ million dollars, and is currently, well, on the road. Of the novel Truman Capote wrote, “That isn’t writing at all, it’s typing.”

Kerouac burned like a slow-to-ignite Roman-Candle, and he died before the last starburst left the sky. His light never has left the sky. My friend’s son just wrote a college paper on Kerouac, and has begun his journey of discovery. Kerouac propelled my journey of discovery as well, but I didn’t understand the depth of experience, or suffering until much later in my life. Jack was a writer fueled by alcohol, and that he wrote as much as he did is something of a miracle. I took him as a wild-man, and as a drunk, but I thought there was more flamboyance to it than pain. Jack Kerouac was a suffering alcoholic, immersed in self-loathing, who lived as spiritually as he could, wrote immensely touching Catholic/Buddhist prose and poetry based on his life and times, and died ignobly, on his suburban Florida couch, of a burst gut. If I could I would canonize him so he’d be officially known as Saint Jack Kerouac. His work was that touching and honest.

Kerouac was known as the “King of the Beatniks,” a title he hated, and though he may not have coined the term, he defined it: “beat,” as in “beatific.”

His books I love the best are: “On the Road,” “Dharma Bums,” “Desolation Angels,” and “Big Sur.” I also re-read his sutra, “The Scripture of the Golden Eternity,” every few years.

Kerouac’s huge collection of spontaneous poetry was, “Mexico City Blues.” Here’s one of its more famous choruses:

211th Chorus, from Mexico City Blues

The wheel of the quivering meat conception

Turns in the void expelling human beings,

Pigs, turtles, frogs, insects, nits,

Mice, lice, lizards, rats, roan

Racinghorses, poxy bubolic pigtics,

Horrible, unnameable lice of vultures,

Murderous attacking dog-armies

Of Africa, Rhinos roaming in the jungle,

Vast boars and huge gigantic bull

Elephants, rams, eagles, condors,

Pones and Porcupines and Pills-

All the endless conception of living beings

Gnashing everywhere in Consciousness

Throughout the ten directions of space

Occupying all the quarters in & out,

From super-microscopic no-bug

To huge Galaxy Lightyear Bowell

Illuminating the sky of one Mind-

Poor! I wish I was free

of that slaving meat wheel

and safe in heaven dead.

(More on St. Jack here: www.jackkerouac.com)

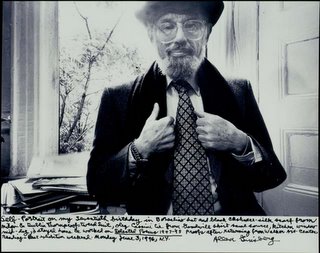

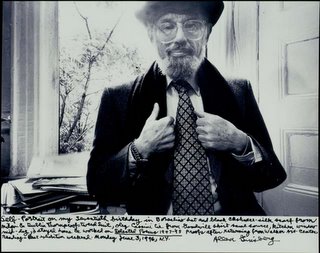

Allen Ginsberg. Ah, Allen - St. Jack’s partner-in-crime, poetic revolutionary, Great American Bard and Bodhisattva, ever-green Allen Ginsberg. Lovely Allen Ginsberg who taught, “First thought, best thought,” but who also taught, “Your first best thought might not be your best first thought.”

Ginsberg was born in Newark, New Jersey, and brought up in Patterson, the home of William Carlos Williams, who revolutionized his generation’s poetic diction. Allen’s father, Louis, was also a poet.

I took to Allen Ginsberg’s work much before I took to him. In the late 50’s/early 60’s he was a shabby, bearded fellow. Not much to look at, in fact rather odd looking, but, oh, how he could write.

Ginsberg was heavily influenced by Walt Whitman, (and was, quite possibly his spiritual descendent,) William Blake, and St. Jack, but was a widely-read scholar and professor of poetry.

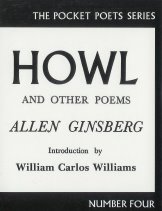

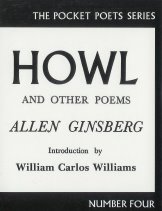

The poem that shot Ginsberg into the stratosphere was, “Howl,” a Whitman-esque paean to, “the best minds of my generation, destroyed by madness.” “Howl,” is a cri de coeur that captures the anguish of the free-spirit in a repressive society. Its stanzas are written according to the poet’s breath, are rough, raw, sometimes funny, and totally compelling. He finishes the poem with a section to Moloch, the beast that eats its children, also known as America; and a coda that has deeply influenced me, in which he announces that all things are holy, and in his fashion goes on to enumerate much of the, “all.” The publication of “Howl” by City Lights Books, a house owned by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, another poet of the generation and founder of America’s first paperback bookstore, resulted in a landmark obscenity trial in 1957 that was handily won by the beatnik boys and girls and their comrades.

Ginsberg was the public relations man, and on many occasions “Clown-Prince,” of the movement. It’s possible that if it were not for Ginsberg, Kerouac wouldn’t have been published. Certainly Gregory Corso, and a host of lesser lights wouldn’t have seen print.

Allen Ginsberg was the most visible “seeker,” of the gang. He was an early user, and strong proponent of mind-altering drugs. There’s a photo of him from the 1960’s carrying a, “Pot is fun,” poster. He chummed around with Kerouac through the marijuana days, William Burroughs through the heroin and yage days, Timothy Leary through the psychedelic days, and I’m sure, all manner of drugged miscreants through all his days. Ginsberg was a Jew who became a student of Hinduism, and finally sought refuge in the Dharma as a follower of Chogyam Trungpa Rimpoche.

Allen was gay, came out early, and made a lifetime cause of gay (and human) rights. He was a non-violent revolutionary, and made no bones about his beliefs. He was crazy when crazy was the best tactic, insightful and precise when those worked. He was tireless. There’s a wonderful TV clip of Allen charming the pants off William F. Buckley, the reptilian editor of the conservative National Review, and pillar of the American intellectual right, that epitomizes Allen’s reach from the heart tactics. (The exchange is captured in the film, “The Life and Times of Allen Ginsberg.”)

Ginsberg was a citizen of those parts of the world that would have him. There were countries that kicked him out – Czechoslovakia, and Cuba – and the powers that were in America would have done without him if they could. He kept an apartment in New York’s lower east side all his life, but spent great deals of time in San Francisco, and Colorado – home of the “Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics,” founded by himself and poet Anne Walman, at Rimpoche’s academy of Buddhism – Naropa.

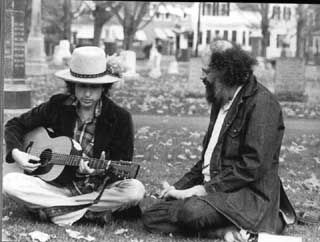

Allen was always au currant, inhabiting and influencing all the art scenes that shook the scene. His friends and students were well known, and unknown – Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the poets of the New York School, the San Francisco Renaissance, and the Russian refuseniks, the American Abstract Expressionist artists, and all too many writers, artists, and musicians. He was the ultimate networker, and loved humanity.

Ginsberg wrote up until the day before he died – not so very long ago, 1997.

Allen Ginsberg was the embodiment of fearless abandon.

I think “Howl,” and “Kaddish,” are his best longer works. “Howl,” was the poem that made me want to be a poet. The Kaddish is the Hebrew prayer for the dead and the poem was written for his mother Naomi. But Allen wrote prolifically, and though his work may be an acquired taste, it’s worth it, and I find something I like in every collection.

From, “Memory Gardens,”

Well, while I’m here I’ll

do the work –

and what’s the work?

To ease the pain of living.

Everything else, drunken

dumbshow.

And here’s a poem I’ve just, today, read for the very first time:

WILD ORPHAN

Blandly mother

takes him strolling

by railroad and by river

-he's the son of the absconded

hot rod angel-

and he imagines cars

and rides them in his dreams,

so lonely growing up among

the imaginary automobiles

and dead souls of Tarrytown

to create

out of his own imagination

the beauty of his wild

forebears-a mythology

he cannot inherit.

Will he later hallucinate

his gods? Waking

among mysteries with

an insane gleam

of recollection?

The recognition-

something so rare

in his soul,

met only in dreams

-nostalgias

of another life.

A question of the soul.

And the injured

losing their injury

in their innocence

-a cock, a cross,

an excellence of love.

And the father grieves

in flophouse

complexities of memory

a thousand miles

away, unknowing

of the unexpected

youthful stranger

bumming toward his door.

(Ginsie’s official site here: www.allenginsberg.org)

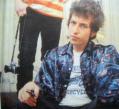

And then, there’s Bob Dylan.

Finally, a voice for my generation who refuses to admit being a voice for anyone except the muse, and that’s probably as it should be.

Bob Dylan, born Robert Zimmerman, in the Iron Range of Hibbing, Minnesota, in 1941.

I was a fan of folk music from the time I got out of high school, but not a big fan until my mentor of the time, Lenny Edelstein, the Director of the Erie Civic Theater, played me a recording of Pete Seeger, Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGee at Carnegie Hall. The folk music we heard over the radio was a white-bread sort of folk music, made palatable for the music buying public. Seeger and company were the real thing, honest and filled with life, and it was obvious. Folk music was the next best thing to the beatniks: out of the mainstream, and populated by people who didn’t seem to give a damn about how they looked or what other people thought, so I paid attention, and eventually heard Bob Dylan.

Dylan was first recorded in 1962, but it was an album of covers – older folk songs – that not too many people caught on to. In ’63, when he was 22 years old, he released, “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” containing 13 songs, of which only two or three were covers or rewritten versions of other writers’ work, and of the rest Dylan gave us five absolute classics: “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Girl of the North Country,” “Masters of War,” “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall,” and, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” Even though I knew the songs, and strummed along to them on my guitar, I didn’t realize the genius contained, but here was a force to be reckoned with. Forty years later the songs have been covered and covered again, show up in Dylan’s concerts, and are as good as new. Then, I just thought they were songs – good one’s, but just more songs of all the songs I wanted to hear, learn, and play.

One night, a couple of years later, 1965, Dylan grabbed me and shook me up. I was drunk as a skunk, hanging out with my intended girlfriend, Cathy. Cathy had actually been Geoff Petersen’s girl, but I’d been enamored of her from first sight, and when Geoff joined the Army I swooped like a hawk. When you get right down to it, Cathy was never really a girlfriend. It’s more like she put up with me because I was already around, and had made myself so damned insistent.

We were lying around her apartment listening to, “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” off the “Bringing it all Back Home,” album. The album contains an out-take of the first two lines of the song that end when Dylan breaks into a laugh. It seems he started the song, and the band forgot to join in, and it cracked him up. I was transfixed by that laugh. I hunkered down in front of the turntable and played those few seconds of lyrics, and that laugh, over and over again. If Cathy hadn’t stopped me I would have listened to it all night. It was the most spontaneous thing I’d ever heard on a record. A mistake, but so human, and Dylan and the producer must have known they had captured something special because they left it on the release.

Much of the album mystified me. Dylan was only five years my senior, but he was so beyond me I didn’t even think about catching up. But it’s an essential Dylan album, and the first work to blow up his fan base. It was his foray into electricity and rock and roll, and if his earlier work revolutionized folk music by presenting a singer/songwriter with a modern sensibility and absolute authority, then “Bringing It All Back Home,” was his first volley into revolutionizing pop music with a poet’s sensibility. The tunes that rhymed June/moon/spoon were about to be chucked right out the window.

The album was released in 1965, has never gone out of circulation, and the tunes are staples in Dylan’s concerts, and primers for most songwriters.

The only song on the album that still mystifies me is, “Gates of Eden.” It seems to be another dream song, but its logic is near impenetrable. But even this song contains a stray verse, and images that are astounding.

The motorcycle black madonna

Two-wheeled gypsy queen

And her silver-studded phantom cause

The gray flannel dwarf to scream

As he weeps to wicked birds of prey

Who pick up on his bread crumb sins

And there are no sins inside the Gates of Eden.

I’m not going to try to parse that verse, but will say that the “gray flannel dwarf,” is probably an allusion to a best-selling book of the 1950’s, followed by a movie with Gregory Peck titled, “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,” that’s about the American conformist rat-race society. Dylan’s lyrics have always been informed by popular culture, and he’s even written a song that features Gregory Peck.

The truth though is that nothing on that album knocked me out as much as the laugh, and the cultural significance of Dylan’s move into pop music was totally lost on me until much later.

I didn’t pay attention to Dylan again until I was out of the Army in 1969, and even then he was more on the periphery than front and center for most everyone except the hard-core fans who wanted him back in the fold acting the prophet and voice for their lives and causes. He’d dropped out of public view for personal reasons, and to raise a family, and even though he released albums they leaned toward Country, and didn’t have anything to do with the “sex, drugs, rock & roll,” and anti-war, anti-establishment activism that had taken over the US. Dylan was quoted, but not his current work. One of his lyrics was even applied to a group of young, violent revolutionaries called the “Weathermen.” The lyric stated, “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

In 1975, Dylan released his masterpiece, “Blood on the Tracks,” and everyone took notice. By that time we’d been through it all. Flower power had lost to the Hell’s Angels at a Rolling Stones concert in California, where the Angels, hired as security guards had beaten an audience member to death; we’d all been in and out of too many relationships; the war dragged on; and I was mostly laying low, getting laid and loaded, and trying to earn a living.

I was living in Santa Fe, New Mexico, when, “Blood on the Tracks,” came out. Naomi, a beat sort of gal from the East Coast who had changed her name from something more prosaic, was the first of our gang to buy a copy, and though I’d told her I didn’t much care for Dylan, she insisted I come over to her house and give it a listen.

The album captured me. Thirty years later I’m still plumbing that album’s depths, but even then I couldn’t hear a false note, or misplaced word. The songs were about unrequited love, failed relationships, the passage of friends and time, and redemption. They were story songs, written out of personal anguish, but entirely universal. “Blood on the Tracks,” is emotionally mature, lyrically precise, and musically matched; in a word, “brilliant.”

I was forced to revisit the last ten years of Dylan’s output because “Blood on the Tracks,” made it obvious Dylan was writing and performing the most compelling poetry I’d heard since Allen Ginsberg. More compelling, because Dylan had tamed his wild imagination and given us lyrics and tunes that were intelligent, and accessible, and not the “wild yawp,” that still propelled much of Allen’s work.

There have always been two Dylan’s, the public, and the private. He became an international pop sensation at an early age, but struggled, and has been largely successful at keeping his private life out of view. The Dylan persona has been an exercise in personal mythology that began as soon as he left Hibbing for the Big Apple. Even so, if you wanted to learn about Dylan the material was available, and there was no shortage of budding Dylan scholars, and self-appointed private investigators to fuel the fire.

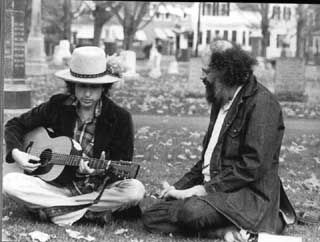

Bob and Allen at Jack's Grave in Lowell, Mass.

I was struck by four aspects. One: Dylan and I shared the same academic credentials – none. Dylan was a college drop-out who found more to learn on the streets, in the songs, and in his own investigations than in any classroom. Two: “He not busy being born is busy dying.” Dylan invented and re-invented himself as the whim, or need arose. Adopted child that I was, I felt allegiance to no one, and had the freedom to make of myself what I would. Three: Dylan had to share what was true and what was invented, and there was truth, sometimes a greater truth, in the invention. Four: Dylan never seemed to give a damn. He’s always done what seemed right for himself, and his art, and the devil take the hindmost. I’m not that fearless, but I find the attitude admirable.

Dylan has been on the public scene over forty years, and even in his mid-sixties he goes on inventing and re-inventing every time he stands on a stage, and he stands on a stage over a hundred times a year. He’s continued creating, lost and won fans, and been pilloried and praised by critics. He’s spent a lifetime, “busy being born.” If one record album equals one volume of poetry, then Dylan has published about 40 volumes, good, bad, and sublime. Last year he published the first volume of his autobiography, “Chronicles, Volume I,” which spent 19 weeks on the New York Times’ Best Sellers list, hit number 2 on the Amazon.com list, and continues to hover in the mid-100’s; Martin Scorsese released a 4 ½ hour documentary covering his first 5 years of public art; and he doesn’t seem to be slowing down all that much.

Here are two pieces from Mr. Dylan, the first a love song, circa 1971, that also strikes me with the beauty of its nature lyrics:

TOMORROW IS A LONG TIME

If today was not an endless highway,

If tonight was not a crooked trail,

If tomorrow wasn't such a long time,

Then lonesome would mean nothing to you at all.

Yes, and only if my own true love was waitin',

Yes, and if I could hear her heart a-softly poundin',

Only if she was lyin' by me,

Then I'd lie in my bed once again.

I can't see my reflection in the waters,

I can't speak the sounds that show no pain,

I can't hear the echo of my footsteps,

Or can't remember the sound of my own name.

Yes, and only if my own true love was waitin',

Yes, and if I could hear her heart a-softly poundin',

Only if she was lyin' by me,

Then I'd lie in my bed once again.

There's beauty in the silver, singin' river,

There's beauty in the sunrise in the sky,

But none of these and nothing else can touch the beauty

That I remember in my true love's eyes.

Yes, and only if my own true love was waitin',

Yes, and if I could hear her heart a-softly poundin',

Only if she was lyin' by me,

Then I'd lie in my bed once again.

And from 1997,

TRYIN’ TO GET TO HEAVEN

The air is getting hotter

There's a rumbling in the skies

I've been wading through the high muddy water

With the heat rising in my eyes

Every day your memory grows dimmer

It doesn't haunt me like it did before

I've been walking through the middle of nowhere

Trying to get to heaven before they close the door

When I was in Missouri

They would not let me be

I had to leave there in a hurry

I only saw what they let me see

You broke a heart that loved you

Now you can seal up the book and not write anymore

I've been walking that lonesome valley

Trying to get to heaven before they close the door

People on the platforms

Waiting for the trains

I can hear their hearts a-beatin'

Like pendulums swinging on chains

When you think that you lost everything

You find out you can always lose a little more

I'm just going down the road feeling bad

Trying to get to heaven before they close the door

I'm going down the river

Down to New Orleans

They tell me everything is gonna be all right

But I don't know what "all right" even means

I was riding in a buggy with Miss Mary-Jane

Miss Mary-Jane got a house in Baltimore

I been all around the world, boys

Now I'm trying to get to heaven before they close the door

Gonna sleep down in the parlor

And relive my dreams

I'll close my eyes and I wonder

If everything is as hollow as it seems

Some trains don't pull no gamblers

No midnight ramblers, like they did before

I been to Sugar Town, I shook the sugar down

Now I'm trying to get to heaven before they close the door.

What a difference twenty years makes. And, of course, the lyrics are only half the story. Dylan is, above all, a songwriter.

It appears I’ve given much more space to Dylan than the other writers. Ah, well. Dylan once said of his mentor, Woody Guthrie, that a person could learn how to live by listening to his songs. I feel the same way about Bob.

(Bob’s official site: www.bobdylan.com)

So, Juhi, that’s the main list. I certainly didn’t expect to be so long winded, but it’s been great fun delving into the past, and revisiting my literary heroes. These five writers shaped me, but the list of authors who have filled the bowl is long, and even includes a few women, unlike the, “Gang of 5:”

Robert Bly

Hafiz

Doris Lessing

The Diane’s DiPrima and Wakowski

Anne Waldman

Paul Blackburn

Jerome Rothenberg

Omar Khayam

Samuel Beckett…

…And on, and on, and on – a lifetime of influences, a lifetime of arguments, a life-long passion, from Homer to Dickenson to Mario Puzo – the gift of reading.

If you got this far, hope you enjoyed, and thanks again for asking,

Richard

PS: But, please, don’t ask me to recommend any movies!

Your indulgences. This is a long entry, and as such probably breaks all the rules of blogdom. Are there rules?

My young friend, Juhi, asked me to recommend a few books to her. I went off the deep-end and produced the following:

November 30 – December 12, 2005

Hyderabad, India

Dear Juhi,

Thanks for asking me to recommend a few books to you. What sounded like a very simple request became more and more complicated as I thought about it, and I’m afraid I’m going to stick you with a hybrid of book list and memoir that goes on much longer than I thought it would.

More than any other activity, reading has been a constant in my life. Some time before I began pre-school, and I have no idea why I had the urge, I begged my parents to teach me to read. Thinking they were doing the right thing by not wanting me to get ahead of my peers, they told me that as soon as I started school I’d be able to read. I awaited the day. According to family legend I returned home after my first day of school, picked up a book, and sat myself down – ready for the great adventure to begin. Within minutes I was desolate, and in tears. The marks on the page were as incomprehensible as ever – I had been betrayed. A day of school had gone by, and still I could not read. Of course, I recovered, and family legend continues that I actually learned to read on road trips by puzzling out the advertising on bill-boards along the roadside. I certainly remember the peculiar American advertisements for “Burma Shave,” a nationally known shaving cream. They were sets of six small red signs with white print, posted about 100 feet apart on rural highways, and you had to be fairly quick to spot and read them. The slogans were corny, but fun: “Doesn’t kiss you…Like she useter?...Perhaps she’s seen…A different rooster…Burma Shave!” The whole family would watch out for them, but I got to shout the slogans out.

I remember only one book from my early childhood, an illustrated collection of fairy tales, and the story that stood out was that of Jack and the Beanstalk. As I recall, Jack traded the family cow for magic seeds that grew into a great beanstalk that Jack climbed to a Giant’s lair. He came across a bag of gold and thought he’d steal it to make reparation for the poorly bartered cow. Although he used all his guile, when he got close to the Giant, and the gold, he was, literally “sniffed out,” and the Giant announced his discovery with, “Fee, Fie, Fo, Fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman!” Jack eventually got the gold, and fled down the vine. The Giant gave chase, but Jack was able to take an axe to the beanstalk, and sever it, and the Giant fell to his death. The moral is a puzzle: Barter well, but if you don’t its ok to steal from a Giant – and kill him while making your get-away.

The first “young reader’s” book I read cover to cover, and I stayed up well past bed time to do it, was, “The Guadalcanal Diary,” by Richard Tregaski – a soldier’s account of a particularly awful series of battles in the South Pacific during World War II.

The first book I ever purchased was, “Al Capone,” a biography of the American gangster – one of the first of the Mafiosi. What a cast of characters, and what names: Dion O’Banion, Big Jim Collosimo, Frank Nitty, and Big Al himself. Really bad guys, and I’m still fascinated by the history of organized crime.

As a “good, Catholic,” boy I also read voraciously in Butler’s “Lives of the Saints.” These were supposed to be moral tales describing the trials and victories of leading a Christian life, but for me, they were an enthralling, almost pornographic compendium of torture. Many of the stories had to do with the fate of virgins who protected their chastity at all costs, and “soldiers of Christ” who refused to renounce the faith. So many saints dismembered, decapitated, eye-gouged, boiled in oil, stretched on the rack, riddled with arrows, and stoned; an endless, mind-boggling, and particularly juicy list to an over-imaginative youth.

I don’t recommend any of the above, except, perhaps, (and slightly facetiously,) the “Lives of the Saints,” for a look into how weird religious teaching can be.

Fairy tales, war, gangsters, and mutilated saints – what a foundation for a life of reading. And it has been a life of reading in which I’m sure I’ve read at least a book a month (more, really,) since the primer of, “See Jack run…” And what an adventure it’s been. I’ve witnessed the creation of matter; have had a look at the farthest reaches of the universe, and through all the permutations of human behavior committed to print!

All of which leads me to a total lack of confidence in recommending a course of reading, or even a simple suggestion of, “You ought to read…” Yes, of course, there are individual books that have moved and shaped me, but they were particular for a time and a need, and it would be presumptuous of me to determine your time or need, or to waste your time with even the first fifty pages of something you might find totally irrelevant.

Instead, I’d like to tell you about the authors who have captured me for a lifetime, mention the work that led me deeper – even if it may not be the best of their oeuvre, and let you take it from there.

But first, what is it about authors, and was I attracted to the literature because of the author, or to the author through the literature? It turns out a combination of both, but, oh, how I loved those authors.

Why?

I wrote above that I was a, “good Catholic boy,” and that’s true enough, but without enough truth.

I was baptized, and raised a Catholic, went to church, received the sacraments, but from the age of seven to fourteen it was all a painful charade. The difficulty came because I was a six-year-old Casanova, and spent a lot of time with the neighborhood girls, “playing doctor,” as it was then called. The play was really about discovering, and enjoying our forbidden bodies – our forbidden sexuality. No religion is comfortable with pleasure, especially physical pleasure, Catholicism is no different, and we knew our play was out-of bounds. We certainly knew enough to keep it hidden in the secret corners of the neighborhood.

Matters were made worse for this “good Catholic boy,” because at age six I was being formally prepared to enter the, “age of reason,” the magic age when we were told we would understand the difference between good and evil, and be expected to live our lives accordingly. This passing from innocence to experience is a Catholic’s first conscious rite of passage, and is part of the genius of the religion.

The preparation for this step into reason was a detailed study of Christianity’s moral code – the Ten Commandments, and indoctrination into an exercise called the “examination of conscience,” in which we reflected on how we may have transgressed. Practical application came by way of a confession of sins, followed by our “First Holy Communion,” at which time we imbibed the mystical body and blood of the Lord, Jesus Christ. The ritualized cannibalism was the easy part. The hard part was the confession of sins during which we met, individually, with a priest, and on our knees detailed our wrong doings, and begged forgiveness; but forgiveness was not assured, and was contingent on honesty in the telling, and sincerity in the repentance. And, there was a fail-safe of sorts to keep us honest: an incomplete or insincere confession was classified as a “mortal sin.” “Mortal,” as in “fatal.” Not physically fatal, but fatal to our souls. If I were to die with a mortal sin staining my soul, my spirit would be cast into hell, there to suffer for eternity. Hell was presented as a real place, and our teachers even claimed the existence of maps – influenced, no doubt, by hell’s great cartographer, Dante.

Embarrassment and fear kept me from telling the priest about my sexual adventures.

I then compounded the matter by taking Communion, thus committing another mortal sin, and repeated the cycle every Confession Friday and Communion Sunday for the next seven years.

I was no longer in a, “state of grace.”

I was doomed.

Redemption has been an obsession ever since. Redemption marks the return to grace. The authors I’m going to mention have all dealt with the urge toward redemption; and I dare say great art is motivated by our need for redemption, be it from “original sin-“ the legacy of the original Fall - sins of the flesh, or sins of the spirit.

At age fourteen Catholics undergo another rite, in which your faith is confirmed, and it’s known, aptly enough, as “Confirmation.” Again, intense study – in fact, the entire seven years between rites were spent in various degrees of preparation – followed by a confession of sins to enter the state of grace necessary to receive the sacrament, and culminating in a public ceremony in which you were questioned as to the tenets of the faith, anointed with oil by your Bishop, lightly slapped to signify the suffering you should be prepared to experience in keeping the faith, (back to the “Lives of the Saints,”) took a new name to mark your identity as an adult Christian, and sent into the world as a “soldier of Christ.”

I was intent on coming clean before I was confirmed. I was intent even as I approached the priest. I was intent as I knelt…and I was devastated as I walked away having failed to summon the courage to rescue my soul. Then, as if in a dream, I went through the ritual motions of confirming a faith that God and I knew I was not strong enough to embrace.

Life pretty much went to hell from there.

I was an adopted child (a whole other story,) and always felt as though I were an outcast. I had failed my religion, and compounded mortal sin upon mortal sin – I was sure that I was excommunicated from the Church, even if ex officio – outcast again – outcast and doomed. Later that year my step-father died, and I was again abandoned.

Abandoned, outcast, and doomed.

The stories I’ve told thus far would probably lead you to believe I was an abnormal child. I don’t think that’s so. I was well loved, my family was well off, and I was engaged in most of the same activities any 7 to 14 year old boy would enjoy. But, I don’t think there’s any accounting for the secret life of childhood and adolescence, and my secret life was fraught with moral and existential dilemmas of an adult level.

I found what I thought were an equally doomed group of friends, and our escape hatches were between book covers, and under bottle caps.

Abandoned, outcast, doomed, and drunk; I found Eugene O’Neil.

Geoff Peterson introduced O’Neil into my life. Geoff was one of my best friends, and we were both interested in the theater. He had hooked up with the local college drama department, and I followed him through the doors.

Geoff was playing the role of the young Eugene O’Neil in, “Ah! Wilderness,” O’Neil’s only comedy, and probably the only O’Neil that the town or college was equipped to handle. O’Neil’s work marks the beginning of serious American drama, and the best of it had to do with his miserable Irish family, or the outcasts and misfits of his equally miserable life. The New York Times described his work as, “…deep, dark, solid, uncompromising and grim.”

I loved everything about Eugene O’Neil. I loved that he was born in a hotel, and was an alcoholic from a family of alcoholics. I loved that his mother was addicted to morphine; that his father was a hack actor; and his brother a Broadway ne’er-do-well. I loved that he had shipped out with the Merchant Marine. And I loved that he suffered for his art. The name I took at my Confirmation, “Eugene,” was secretly for Eugene O’Neil. I got away with it because I had told everyone it was for the current Pope, Pius XII, whose given name was “Eugenio.”

O’Neil died in 1953, and even by then the majority of his work was dated, but the late 1950’s, early ‘60’s saw a revival of his best work. Jason Robards was the actor that embraced O’Neil in those revival years, and his status probably sold as many tickets as the plays. The roles he played were Shakespearian in proportion. There are at least three O’Neil masterpieces I’ve seen performed: “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” “The Iceman Cometh,” and, “A Moon for the Misbegotten,” and they’re beautiful and heart-breaking.

One drunken night at Jim Gallagher’s house, Geoff launched into a monologue culled from, “A Moon for the Misbegotten.” It was a bravura performance, spellbinding, and shattering. At the time we didn’t know that what he was saying was from a play – the s.o.b.

Here are the last few paragraphs:

I had to bring her body East to be buried beside the Old Man. I took a drawing room and hid in it with a case of booze. She was in her coffin in the baggage car. No matter how drunk I got, I couldn't forget that for a minute. I found I couldn't stay alone in the drawing room. It became haunted. I was going crazy. I had to go out and wander up and down the train looking for company. I made such a public nuisance of myself that the conductor threatened if I didn't quit, he'd keep me locked in the drawing room. But I'd spotted one passenger who was used to drunks and could pretend to like them, if there was enough dough in it. She had parlor house written all over her--a blonde pig who looked more like a whore than twenty-five whores, with a face like an overgrown doll's and a come-on smile as cold as a polar bear's feet. I bribed the porter to take a message to her and that night she sneaked into my drawing room. She was bound for New York, too. So every night--for fifty bucks a night--

--How could I? I don't know. But I did. I suppose I had some mad idea she could make me forget--what was in the baggage car ahead.

No, it couldn't have been that. Because I didn't seem to want to forget. It was like some plot I had to carry out. The blonde--she didn't matter. She was only something that belonged in the plot. It was as if I wanted revenge--because I'd been left alone--because I knew I was lost, without any hope left--that all I could do would be drink myself to death, because no one was left who could help me. No, I didn't forget even in that pig's arms! I remembered the last two lines of a lousy tear-jerker song I'd heard when I was a kid kept singing over and over in my brain.

"And baby's cries can’t waken her, in the baggage car ahead. And baby’s cries can’t waken her, in the baggage car ahead. And baby’s cries can’t waken her in the baggage car ahead.”

Jim and I left the room with Geoff huddled on the bed. He’d certainly managed to put a damper on the evening… When I finally found the reference, on the same record album from which Geoff had stolen it, I let it go. It was too much to bring up.

The Gallagher family was a piece of work in itself, and I spent a great deal of my senior year in high-school hanging out at their house – mostly in Jim’s bedroom. Jim’s father, Arthur, was a chronically unemployed alcoholic who spent his time lazing on the couch listening to French language radio, (though he spoke not a word of French,) and reading Spinoza. He was also our beer connection, and would charge us a six-pack for every case he picked up for us. Of course, we paid up. Jim’s elder sister was a wild-child in her own right, and Mrs. Gallagher was a hard worker who kept food on the table, and a roof over their heads, but had no control over her husband or brood. Jim was one of the doomed; a high-school neo-Nazi with a penchant toward marching songs and Gilbert and Sullivan. Once, Jim locked me in his bedroom until I could prove I’d memorized an entire Gilbert and Sullivan song from, “The Sorcerer.” The title was, “John Wellington Wells,” and Jim thought it appropriate to my name. I occasionally recite it as a party piece, to the astonishment of my friends.

Geoff and I fancied ourselves miniature Eugene O’Neil’s, but Geoff had a leg up. Not only had he acted in an O’Neil play, but he was “black Irish,” as was O’Neil, and actually wrote a couple one-act plays. I just drank, smoked, read the collected works and the definitive 800 page biography, and pretended I was as talented and rakish as the great man.

(For more on O’Neil: www.eoneill.com)

Henry Miller was an author (and watercolorist) who may not be so widely read these days. Henry was American born, of Manhattan, in 1891, and knocked around the city until 1930 when he moved to Paris to begin what were his great years of self-discovery. Miller was a Catholic who eschewed all religion and leaned toward an all-encompassing pantheism. Like all the gang Miller was the primary figure in his own works, and his works were wild, though probably wilder than the life that fueled them.

Miller wrote copiously of his sexual escapades, and came perilously close to becoming known as a writer of “dirty books,” and a parody of the dirty old man. “Tropic of Cancer,” published in France in 1934, didn’t make it to the US until 1961, and it immediately became embroiled in a series of obscenity trials finally decided by the US Supreme Court on the same day it was presented.

Miller’s trilogy, “Sexus,” “Plexus,” and “Nexus,” were, according to him, an outpouring of the vilest and most depraved imaginings his psyche could produce. I’ve not read them, but wonder in 2005 how vile they could really be.

He returned to the US in 1940, and eventually settled in Big Sur, California.

I read about “Tropic of Cancer,” well before it was released, and came across it in its original Grove Press Edition in a bookstore in New York City in 1961. I can still see the display of that shiny, red paperback, with its black title in a white circle. I didn’t purchase it because I was with my folks, and was a little afraid that showing interest would tip them off to what their kid was really thinking about, but I was thrilled to see it.

(Grove Press was one of the most courageous publishing houses in America, and enjoyed quite a bit of notoriety and profit from the American publication of, “Lady Chatterley’s Lover;” as well as most of Samuel Beckett, Jean Genet, Federico Garcia Lorca, and a host of other influential, avant-garde, and sometimes scatological authors. Most of the Grove catalogue is still in print. Grove also published, “The Evergreen Review,” arguably America’s most influential literary journal from 1957 – 1968. Grove’s publisher, Barney Rosset, on free speech: “…I feel that personally there hasn’t been a word written or uttered that shouldn’t be published.”)

I was a bit older when I finally got around to “Tropic of Cancer,” and remember “meditating” on the “good bits,” and falling in love with the grit and grime of Miller’s milieu. Here was a guy who was tromping through the muck, and having a glorious time of it.

As much as I liked, “Tropic of Cancer,” and its follow-up, “Tropic of Capricorn,” I loved Henry Miller’s essays. Miller came across as smart, comic, impassioned, and immensely likable. He seemed to like what I liked, and hate what I hated, but with so much more panache than I could ever summon.

“The Air Conditioned Nightmare,” “Stand Still Like the Hummingbird,” “Wisdom of the Heart,” are all wonderful collections, but I’ve read so much Miller, and like him so much I’d recommend just about any of his essay collections except, “The Time of the Assassins,” which is a literary study of Rimbaud, and nowhere near as compelling as his other works.

Here’s what George Orwell wrote of Henry Miller:

"Here in my opinion is the only imaginative prose-writer of the slightest value who has appeared among the English-speaking races for some years past. Even if that is objected to as an overstatement, it will probably be admitted that Miller is a writer out of the ordinary, worth more than a single glance; and after all, he is a completely negative, unconstructive, amoral writer, a mere Jonah, a passive acceptor of evil, a sort of Whitman among the corpses."

And what Henry wrote about art:

"We’re creators by permission, by grace as it were. No one creates alone, of and by himself. An artist is an instrument that registers something already existent, something which belongs to the whole world, and which, if he is an artist, he is compelled to give back to the world."

(Henry here: www.henrymiller.org)

I don’t remember how I came to the beatniks, but they were the enfants terrible of American letters, and enjoyed great notoriety for their work, and their life-styles. I have to speak the names Kerouac, and Ginsberg in the same breath, though they were hugely different people, and writers. Ginsberg gives credit for the beat generation and its revolution of prosody to Kerouac. I don’t think Kerouac gives it to anyone but Dostoevsky, and God. Kerouac and Ginsberg were both, “rake and ramblin’ boys,” and I loved their bad-boy-ness as much as I admired their writing.

Jack Kerouac was from a French-Canadian family of Lowell, Massachusetts, and he called his work as a whole, “The Legend of Duluoz.” “Duluoz,” was not only the name he gave himself in a number of books, but also a pun for “louse,” both a bloodsucking insect, and a contemptible person. Raging alcoholic that he was, Jack had a bit of a self-esteem problem. As of 2001, 27 books comprised the legend, but new volumes tend to pop up as they’re released by his estate. About 20 years ago I took a summer to read most of his work, some of it for the second or third time, and was as enchanted as on first reading, albeit with a lot more understanding of Kerouac’s pain.

Jack worked any number of jobs to support his writing habit. I was impressed that he had been a brakeman for the Union Pacific Railroad, and had shipped out as a Merchant Marine. O’Neil and Kerouac had both shipped out – eventually I was to do the same.

Kerouac’s breakthrough, and still most widely read book was, “On the Road.” These are the adventures of Sal Paradise (Kerouac,) and Dean Moriarity (Neal Cassidy, who played an important role throughout the Legend, and the history of the beat generation.) “On the Road,” ignited Kerouac’s career, and the literary/lifestyle movement of his generation. Here’s a popular quotation:

“The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn, like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars..."

Jack wrote, “On the Road,” in a marathon session, typed on a 120 foot long paper scroll. The scroll was purchased in 2001 for 2 ½ million dollars, and is currently, well, on the road. Of the novel Truman Capote wrote, “That isn’t writing at all, it’s typing.”

Kerouac burned like a slow-to-ignite Roman-Candle, and he died before the last starburst left the sky. His light never has left the sky. My friend’s son just wrote a college paper on Kerouac, and has begun his journey of discovery. Kerouac propelled my journey of discovery as well, but I didn’t understand the depth of experience, or suffering until much later in my life. Jack was a writer fueled by alcohol, and that he wrote as much as he did is something of a miracle. I took him as a wild-man, and as a drunk, but I thought there was more flamboyance to it than pain. Jack Kerouac was a suffering alcoholic, immersed in self-loathing, who lived as spiritually as he could, wrote immensely touching Catholic/Buddhist prose and poetry based on his life and times, and died ignobly, on his suburban Florida couch, of a burst gut. If I could I would canonize him so he’d be officially known as Saint Jack Kerouac. His work was that touching and honest.

Kerouac was known as the “King of the Beatniks,” a title he hated, and though he may not have coined the term, he defined it: “beat,” as in “beatific.”

His books I love the best are: “On the Road,” “Dharma Bums,” “Desolation Angels,” and “Big Sur.” I also re-read his sutra, “The Scripture of the Golden Eternity,” every few years.

Kerouac’s huge collection of spontaneous poetry was, “Mexico City Blues.” Here’s one of its more famous choruses:

211th Chorus, from Mexico City Blues

The wheel of the quivering meat conception

Turns in the void expelling human beings,

Pigs, turtles, frogs, insects, nits,

Mice, lice, lizards, rats, roan

Racinghorses, poxy bubolic pigtics,

Horrible, unnameable lice of vultures,

Murderous attacking dog-armies

Of Africa, Rhinos roaming in the jungle,

Vast boars and huge gigantic bull

Elephants, rams, eagles, condors,

Pones and Porcupines and Pills-

All the endless conception of living beings

Gnashing everywhere in Consciousness

Throughout the ten directions of space

Occupying all the quarters in & out,

From super-microscopic no-bug

To huge Galaxy Lightyear Bowell

Illuminating the sky of one Mind-

Poor! I wish I was free

of that slaving meat wheel

and safe in heaven dead.

(More on St. Jack here: www.jackkerouac.com)

Allen Ginsberg. Ah, Allen - St. Jack’s partner-in-crime, poetic revolutionary, Great American Bard and Bodhisattva, ever-green Allen Ginsberg. Lovely Allen Ginsberg who taught, “First thought, best thought,” but who also taught, “Your first best thought might not be your best first thought.”

Ginsberg was born in Newark, New Jersey, and brought up in Patterson, the home of William Carlos Williams, who revolutionized his generation’s poetic diction. Allen’s father, Louis, was also a poet.

I took to Allen Ginsberg’s work much before I took to him. In the late 50’s/early 60’s he was a shabby, bearded fellow. Not much to look at, in fact rather odd looking, but, oh, how he could write.

Ginsberg was heavily influenced by Walt Whitman, (and was, quite possibly his spiritual descendent,) William Blake, and St. Jack, but was a widely-read scholar and professor of poetry.

The poem that shot Ginsberg into the stratosphere was, “Howl,” a Whitman-esque paean to, “the best minds of my generation, destroyed by madness.” “Howl,” is a cri de coeur that captures the anguish of the free-spirit in a repressive society. Its stanzas are written according to the poet’s breath, are rough, raw, sometimes funny, and totally compelling. He finishes the poem with a section to Moloch, the beast that eats its children, also known as America; and a coda that has deeply influenced me, in which he announces that all things are holy, and in his fashion goes on to enumerate much of the, “all.” The publication of “Howl” by City Lights Books, a house owned by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, another poet of the generation and founder of America’s first paperback bookstore, resulted in a landmark obscenity trial in 1957 that was handily won by the beatnik boys and girls and their comrades.

Ginsberg was the public relations man, and on many occasions “Clown-Prince,” of the movement. It’s possible that if it were not for Ginsberg, Kerouac wouldn’t have been published. Certainly Gregory Corso, and a host of lesser lights wouldn’t have seen print.

Allen Ginsberg was the most visible “seeker,” of the gang. He was an early user, and strong proponent of mind-altering drugs. There’s a photo of him from the 1960’s carrying a, “Pot is fun,” poster. He chummed around with Kerouac through the marijuana days, William Burroughs through the heroin and yage days, Timothy Leary through the psychedelic days, and I’m sure, all manner of drugged miscreants through all his days. Ginsberg was a Jew who became a student of Hinduism, and finally sought refuge in the Dharma as a follower of Chogyam Trungpa Rimpoche.

Allen was gay, came out early, and made a lifetime cause of gay (and human) rights. He was a non-violent revolutionary, and made no bones about his beliefs. He was crazy when crazy was the best tactic, insightful and precise when those worked. He was tireless. There’s a wonderful TV clip of Allen charming the pants off William F. Buckley, the reptilian editor of the conservative National Review, and pillar of the American intellectual right, that epitomizes Allen’s reach from the heart tactics. (The exchange is captured in the film, “The Life and Times of Allen Ginsberg.”)

Ginsberg was a citizen of those parts of the world that would have him. There were countries that kicked him out – Czechoslovakia, and Cuba – and the powers that were in America would have done without him if they could. He kept an apartment in New York’s lower east side all his life, but spent great deals of time in San Francisco, and Colorado – home of the “Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics,” founded by himself and poet Anne Walman, at Rimpoche’s academy of Buddhism – Naropa.

Allen was always au currant, inhabiting and influencing all the art scenes that shook the scene. His friends and students were well known, and unknown – Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the poets of the New York School, the San Francisco Renaissance, and the Russian refuseniks, the American Abstract Expressionist artists, and all too many writers, artists, and musicians. He was the ultimate networker, and loved humanity.

Ginsberg wrote up until the day before he died – not so very long ago, 1997.

Allen Ginsberg was the embodiment of fearless abandon.

I think “Howl,” and “Kaddish,” are his best longer works. “Howl,” was the poem that made me want to be a poet. The Kaddish is the Hebrew prayer for the dead and the poem was written for his mother Naomi. But Allen wrote prolifically, and though his work may be an acquired taste, it’s worth it, and I find something I like in every collection.

From, “Memory Gardens,”

Well, while I’m here I’ll

do the work –

and what’s the work?

To ease the pain of living.

Everything else, drunken

dumbshow.

And here’s a poem I’ve just, today, read for the very first time:

WILD ORPHAN

Blandly mother

takes him strolling

by railroad and by river

-he's the son of the absconded

hot rod angel-

and he imagines cars

and rides them in his dreams,

so lonely growing up among

the imaginary automobiles

and dead souls of Tarrytown

to create

out of his own imagination

the beauty of his wild

forebears-a mythology

he cannot inherit.

Will he later hallucinate

his gods? Waking

among mysteries with

an insane gleam

of recollection?

The recognition-

something so rare

in his soul,

met only in dreams

-nostalgias

of another life.

A question of the soul.

And the injured

losing their injury

in their innocence

-a cock, a cross,

an excellence of love.

And the father grieves

in flophouse

complexities of memory

a thousand miles

away, unknowing

of the unexpected

youthful stranger

bumming toward his door.

(Ginsie’s official site here: www.allenginsberg.org)

And then, there’s Bob Dylan.

Finally, a voice for my generation who refuses to admit being a voice for anyone except the muse, and that’s probably as it should be.

Bob Dylan, born Robert Zimmerman, in the Iron Range of Hibbing, Minnesota, in 1941.

I was a fan of folk music from the time I got out of high school, but not a big fan until my mentor of the time, Lenny Edelstein, the Director of the Erie Civic Theater, played me a recording of Pete Seeger, Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGee at Carnegie Hall. The folk music we heard over the radio was a white-bread sort of folk music, made palatable for the music buying public. Seeger and company were the real thing, honest and filled with life, and it was obvious. Folk music was the next best thing to the beatniks: out of the mainstream, and populated by people who didn’t seem to give a damn about how they looked or what other people thought, so I paid attention, and eventually heard Bob Dylan.

Dylan was first recorded in 1962, but it was an album of covers – older folk songs – that not too many people caught on to. In ’63, when he was 22 years old, he released, “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” containing 13 songs, of which only two or three were covers or rewritten versions of other writers’ work, and of the rest Dylan gave us five absolute classics: “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Girl of the North Country,” “Masters of War,” “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall,” and, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” Even though I knew the songs, and strummed along to them on my guitar, I didn’t realize the genius contained, but here was a force to be reckoned with. Forty years later the songs have been covered and covered again, show up in Dylan’s concerts, and are as good as new. Then, I just thought they were songs – good one’s, but just more songs of all the songs I wanted to hear, learn, and play.

One night, a couple of years later, 1965, Dylan grabbed me and shook me up. I was drunk as a skunk, hanging out with my intended girlfriend, Cathy. Cathy had actually been Geoff Petersen’s girl, but I’d been enamored of her from first sight, and when Geoff joined the Army I swooped like a hawk. When you get right down to it, Cathy was never really a girlfriend. It’s more like she put up with me because I was already around, and had made myself so damned insistent.

We were lying around her apartment listening to, “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” off the “Bringing it all Back Home,” album. The album contains an out-take of the first two lines of the song that end when Dylan breaks into a laugh. It seems he started the song, and the band forgot to join in, and it cracked him up. I was transfixed by that laugh. I hunkered down in front of the turntable and played those few seconds of lyrics, and that laugh, over and over again. If Cathy hadn’t stopped me I would have listened to it all night. It was the most spontaneous thing I’d ever heard on a record. A mistake, but so human, and Dylan and the producer must have known they had captured something special because they left it on the release.