THE BEARDS, GUIDO, AND ME

“A hat should never have a bigger personality than the person underneath it.”

----------Richard Altenbernd

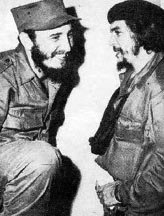

February 6, 1959. I was twelve years old. Edward R. Murrow was still on TV, and his “Person to Person,” show was regular viewing for our family. On this particular Friday night Murrow was to interview Fidel Castro, and we were gathered around the tube. Fidel had only been in Havana for a month, and this was to be a major event interview. My folks were pretty excited because it seemed like history was about to be made in our own living room.

I don’t recall knowing much about the Cuban Revolution prior to the broadcast, but it became an important part of my political education post-broadcast, and a more important part of my fantasy life before the broadcast was even over.

Fidel chose to be interviewed in a suite at the Havana Hilton. Very plush digs after years in the Cuban wilderness, and an interesting statement about victors and spoils that wasn’t completely lost on me. I remember him being dressed in a silk bathrobe, and gripping a cigar; though I’ve since read he was actually wearing pajamas. (I can't find a photo anywhere.) Bathrobe, or pj’s, it was all a little bizarre.

I have no idea what Murrow and Castro talked about, but I recall news clips of the revolutionaries entering the city. The tone of the clips was joyous, and the laughing barbudos, the Beards, on top of their tanks, decked out in fatigues, berets, straw hats, and stogies made revolution look like a party, and then Fidel made it look like a slumber party. The images were the reality; whatever the commentators or talking heads had to say didn’t register. I was entranced, and by the next weekend I was to become a walking advertisement for the Revolution.

There were two stores I had to hit. One was the Army Surplus Store for one of those boxy fatigue caps like Fidel wore; the other was the local joke store to pick up a rubber cigar. Neither proved to be a problem, but then I had to figure out how to keep the cigar in my mouth. Rubber cigars taste like, well, rubber, and even in my fervor that wouldn’t do. Somehow I came up with a black, plastic cigar holder – inauthentic, but it did the trick.

By the next Saturday I was walking around the neighborhood like a little Fidel, but there was no pay-off. I don’t recall the other kids or the adults paying any attention, in fact, I think my friends were avoiding me, so what was the use. Besides, the infamous “stadium trials,” were becoming big news and even as a twelve year old I could smell the rat the Revolution was becoming. I also had other things to do than impersonate Fidel.

I don’t know what happened to the hat, but I kept the cigar for Groucho Marx routines – I already had the glasses and moustache combo from previous trips to the joke store.

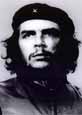

The newsreel images stayed with me though, and the most enduring of them – a gold mine to t-shirt artists, and agitators of every stripe – were of Che, the patron saint.

I was in the Army in 1968 when the whole world seemed to be exploding with revolutionary activity, and I got my hands on a huge black and white poster of Che, in beret, but sans cigar – an iconographic shot. I hung it behind my bunk wondering when, or if, my superiors would ever catch on. One night during a surprise inspection, one of my sergeants took a good look at it, and then a good look at me, at attention and dressed in boxers and a t-shirt, and asked what LSD smoking rock star that was supposed to be. The question was rhetorical, and I’m not sure what the point was, but I was spared having to answer. The poster stayed up for weeks with no one commenting and, once again, what was the use.

Later on I got my first beret from an English sharpshooter who was visiting our base. He’d run out of money in a local gasthaus and I bailed him out in exchange for the beret. The bad news was it was green, and I had to be very careful about where I wore it, lest I be accused of impersonating the elite of the Special Forces. I wore it on leave, and while skulking around the hashish ridden, late-night barracks, and I thought I was just too cool.

I’ve never gotten tired of Che, mostly because he was so good looking, and he died before he had a chance to disappoint me. I’ve still got a drawer full of t-shirts I never wear, but I have been wearing a beret for years – the black variety. I even had one decorated with a tiny red star, but in Chicago in 1970 that was a little too obvious. I switched out for a black bowler – truly ridiculous, especially when combined with a faux fur coat, suede boots, and a ten foot long magenta scarf.

Forty-seven post-Revolution years later I’m just waiting for Fidel to pass away. I like to hope the Cuban people will eventually get the Revolution they deserve, but maybe they have, and what they’ll get next is Ronald McDonald in a black beret with a tiny red star.

March, 1963. I was a junior in high-school, and well along the road to perdition. Geoff Petersen and I were self-styled artistes of a beatnik bent and on the lookout for anything that would enhance our bona-fides. Geoff had somehow been able to see, “La Dolce Vita,” and was excited that “8 ½” had opened at a mainstream theater downtown. How that happened is a mystery of film distribution. I don’t think the theater owners were looking for a run on tickets for an Italian art film in Erie, Pennsylvania; but it was our good luck.

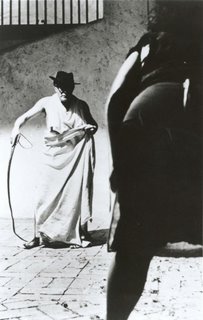

Geoff and I made it to the first Saturday matinee. I think we may have been the only people in the theater. The film rolled, and we watched, but it was pretty much incomprehensible, and I kept nodding off. What really caught me was the look of Marcello Mastroianni as Guido, the protagonist. Oh my, but he was decadent and dapper. His normal costume was a black suit, white shirt, black tie, black horn-rimmed glasses, and an undersized black cowboy hat – or what appeared to be a cowboy hat. Hat designers probably have a name for the exact model he was wearing. And there was one scene that popped my eyes wide open: Guido in a Roman bath, draped in a white sheet, wearing his hat and glasses, and cracking a bullwhip at one of Fellini's beastie women. I didn’t know what the scene was all about, but the image was all.

Geoff left after the first showing, but those were the days when one ticket bought you as many shows as you could sit through, and I stayed for a second viewing. Even while more alert the movie was incomprehensible, and I left before it was over, but I walked out of that theater with a new sartorial model.

I didn’t need the suit, or the sheet, that was overkill, and I was going after essentials rather than the whole outfit. I already had a bullwhip, a souvenir from a family trip to Mexico, so that was no problem. I found the hat in the attic. It was a woman’s hat, probably an out-of-style cast off of my mom’s, but it fit, and with some artistic shaping it became a reasonable facsimile of Guido’s. The glasses were a lot tougher.

I didn’t want frames without lenses – too hokey, even in this there was a limit to outrageousness – and though I searched for black horn rims with plain glass, they weren't available. The only thing I could figure out was to get glasses prescribed. This was going to be difficult because my vision was a perfect 20/20.

I told my mom I was having some trouble reading, that the print was a little blurry. As this came straight out of the blue she didn’t react immediately and suggested that maybe my eyes were tired. “No, no, I’m really having trouble seeing.” A week passed, and after a little research I escalated to: “I’ve got a headache, I think I need glasses.” An appointment was made.

The optometrist couldn’t find anything wrong. I had hesitated over the eye charts, but not enough to raise any red flags, and my eyeballs were given a clean bill of health with the caveat that, “There may be a very small problem, but if I were to prescribe glasses the lenses wouldn’t be much different than plain glass.” It was the, “much different,” that I grabbed onto. “I really need these glasses; I think they’d really make a difference. I think I’d even do better in school.” I wasn’t doing too well as it was, (where was it written that artistes had to study,) so that was the bit that got my mom to a reluctant, “Well, if you think it will help…” Bingo!

Now for the frames: My mom thought tortoise shell were the way to go. Of course tortoise shell would have been the totally wrong way to go; Guido had to have black horn-rims, and at that point I would have begged, but my mom’s unenthusiastic, “They’re your glasses…,” was all the go ahead I needed. Bingo! again, and within a few days I had what I needed. The biggest problem was I was going to have to wear them in more than my Guido-guise, but only when someone was looking.

The only full length mirror in the house was in my mom’s bedroom. On Saturday, after she’d gone out shopping I had a chance to check my ensemble, bullwhip and all. I struck as many poses as possible: arms crossed holding whip, whip unfurled to the rear, whip unfurled to the front, back turned while looking over shoulder.

Perfect.

But where was I going to go?

As it turned out, just about nowhere.

I modeled the outfit for Geoff, but he was way too cool to approve. Geoff never thought much of the make-shift burnoose I sported around after “Lawrence of Arabia,” either.

I went to a party or two, without the whip, even introduced myself as "Guido," but made no great impact, so my Guido gear ended up going the way of Fidel’s fatigue cap. Tell you the truth, though, if I were to ever come across that style hat I’d definitely check it out, and if I liked the look…

The glasses? I lost them after a few weeks, and my mom, bless her heart, never mentioned them.

I was about to get interested in bullfighters anyway…

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home